Mapping a Successful Path to Label Optimization

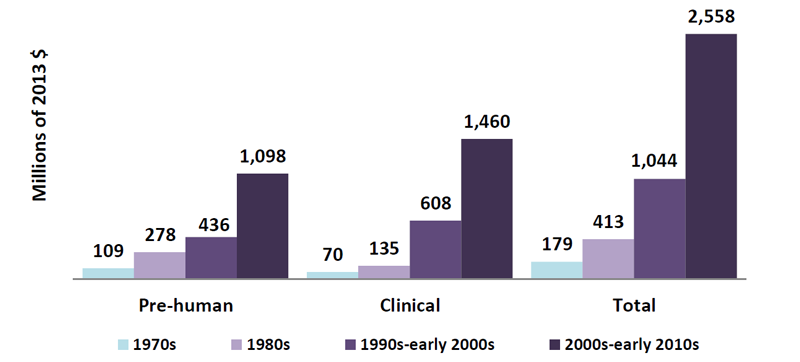

Bringing a drug to market is a long and expensive process. An analysis by the Tufts Center for the Study of Drug Development estimated the total cost of development from discovery to commercialization at $2.6 billion over the course of about 10 years (based primarily on big pharma companies). This represents more than a 10‑fold increase since the 1970s, when a drug could be developed from bench to bedside for less than $200 million (Figure 1).1 Others estimate the cost to commercialize a drug to be much lower (< $1 billion when they consider small biotech companies),2 yet it is generally accepted that the cost of drug development is on the rise. A major driver of those rising costs is the money spent on drug candidates that never make it to market because of safety concerns or lack of efficacy. The bottom line is that there is no room for costly mistakes, miscalculations, or inefficiencies in the drug development process.

Bringing a drug to market is a long and expensive process. An analysis by the Tufts Center for the Study of Drug Development estimated the total cost of development from discovery to commercialization at $2.6 billion over the course of about 10 years (based primarily on big pharma companies). This represents more than a 10‑fold increase since the 1970s, when a drug could be developed from bench to bedside for less than $200 million (Figure 1).1 Others estimate the cost to commercialize a drug to be much lower (< $1 billion when they consider small biotech companies),2 yet it is generally accepted that the cost of drug development is on the rise. A major driver of those rising costs is the money spent on drug candidates that never make it to market because of safety concerns or lack of efficacy. The bottom line is that there is no room for costly mistakes, miscalculations, or inefficiencies in the drug development process.

Figure 1. Growth in capitalized research and development costs per approved new compound. Reprinted from J Health Econ, 47, DiMasi JA, Grabowski HG, Hansen RW, Innovation in the pharmaceutical industry: new estimates of R&D Costs, 20-33, Copyright 2016, with permission from Elsevier.1

Another reality facing drug makers in the 21st century is a dramatic increase in competition compared with just a decade or two ago. Drug development pipelines are brimming with hundreds of similar compounds—all vying for a piece of the pie. Those pipelines are being fueled by the ever-increasing speed at which medical research is discovering the underlying pathophysiology of complex diseases and identifying new therapeutic targets.

As a result of the fast pace of scientific discovery, the therapeutic landscape for many of the most common diseases is also changing rapidly. Take chronic hepatitis C, for example. Less than a decade ago the standard of care was immunotherapy with interferon plus ribavirin, which delayed disease progression. Today, combinations of oral, direct, antiviral drugs are the standard of care, and they offer a cure. Metastatic melanoma is another good example. Up until 2011, dacarbazine, an old chemotherapy drug, remained the standard first-line therapy for the majority of patients. Since then, the FDA has approved 7 new therapies for melanoma, including immune checkpoint inhibitors, BRAF inhibitors, and a MEK inhibitor, that have completely altered the therapeutic landscape.3 These examples highlight why speed and efficiency are critical for successful drug development and why the rate of success for new molecular entities entering phase 1 clinical trials has dropped to only ~12%.1

In this highly competitive and rapidly changing environment, what are the critical success factors for drug developers today? As regulatory and market access consultants to both small biotech and big pharma companies, our mission is to help our clients avoid pitfalls and costly mistakes. Here are a few of the most important success factors to keep in mind:

- Early in the clinical development process, clearly define the target indication and the data needed to support it relative to the anticipated unmet medical need and competitive landscape at the time of launch

- Build a well-functioning multidisciplinary team that is able to infuse patient and payer insights in the early phases of development

- Early on, establish collaborations with outside stakeholders, including thought leaders at leading research institutions and medical centers, payers, and regulatory authorities

- Define the optimal product profile with the end user and market(s) in mind; this should be a dynamic document that is reevaluated frequently by all stakeholders to ensure adequate and timely adaptation to shifting market dynamics and new data

So how does one ensure that these key success factors are baked into the process? The answer lies in building a successful Label Optimization Strategy and a Target Product Profile (TPP)—a strategic document that guides drug development from discovery to commercialization. At its core, the TPP is the blueprint for a drug development program. It sets the parameters and defines the goals for the program with the end user (both patients and healthcare providers), desired market(s), and payers in mind.4,5 But, despite these advantages, the TPP is often underutilized and overlooked by companies both big and small. Our next blog will discuss how to utilize a dynamic TPP to its full potential.

Jeff Riegel, PhD, combines his scientific expertise with more than 20 years of global healthcare agency experience to guide medical and regulatory communication strategies for biopharma companies large and small. Jeff has developed strategies, messages, and presentations for multiple FDA Advisory Committee meetings. He also directs publications planning and execution in oncology and other therapeutic areas. Connect with Jeff on LinkedIn.

Jeff Riegel, PhD, combines his scientific expertise with more than 20 years of global healthcare agency experience to guide medical and regulatory communication strategies for biopharma companies large and small. Jeff has developed strategies, messages, and presentations for multiple FDA Advisory Committee meetings. He also directs publications planning and execution in oncology and other therapeutic areas. Connect with Jeff on LinkedIn.

References

- DiMasi JA, Grabowski HG, Hansen RW. Innovation in the pharmaceutical industry: new estimates of R&D Costs. J Health Econ. 2016;47:20-33.

- Prasad V and Mailankody S. Research and development spending to bring a single cancer drug to market and revenues after approval. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177(11):1569-1575.

- New Therapies Are Changing the Outlook for Advanced Melanoma. National Cancer Institute. http://www.cancer.gov/types/skin/research/advanced-melanoma-therapies Accessed August 13, 2015.

- Lambert WJ. Considerations in developing a target product profile for parenteral pharmaceutical products. AAPS PharmSciTech. 2010;11(3):1476-1481.

- Target Product Profile — A Strategic Development Process Tool. Food and Drug Administration Draft Guidance. 2007. http://www.fda.gov/downloads/drugs/guidancecomplianceregulatoryinformation/guidances/ucm080593.pdf. Accessed August 13, 2015.