The Not-So-Far-Out Therapeutic Promise of Psychedelics

Introduction

Throughout history, humans have had a complex relationship with psychedelics. For millennia, ancient indigenous cultures used them for spiritual and healing purposes. For example, in 2007, archaeologists in Spain discovered mushrooms found at a burial site dated more than 7,000 years old. The mushrooms found at the site were identified as psilocybin, a type of psychedelic mushroom. Fast forward to today, and psychedelics are still in use for spiritual and mystical experiences but are also being studied more scientifically as pharmacotherapy for various psychological conditions, including anxiety, depression, posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), dependency/addiction, eating disorders, and end-of-life distress. In fact, the FDA even released a draft guidance to industry for designing clinical trials for psychedelic drugs.

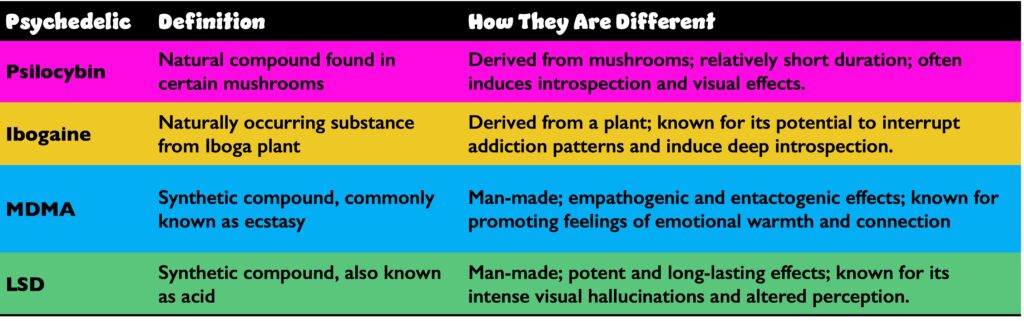

What Are Psychedelics?

Psychedelics are derived from plants and fungi, but some are also synthesized in the lab. Psilocybin, the most studied psychedelic comes from fungi, which are unique organisms that are neither plants nor animals. They share some characteristics with plants, such as the ability to photosynthesize, but they also share some characteristics with animals, such as the ability to digest food. Computational phylogenetics have revealed that fungi split from animals about 1.538 billion years ago, whereas plants split from animals about 1.547 billion years ago. This means fungi split from animals 9 million years after plants did, meaning that fungi are actually more closely related to animals/humans than to plants.

LSD, lysergic acid diethylamide; MDMA, 3,4-Methylenedioxymethamphetamine.

Psychedelics modulate brain activity and have been associated with therapeutic effects such as increased neuroplasticity and modulation of reward pathways, not dissimilar to the mechanism of action underlying conventional antidepressants. Psychedelics work by binding to the serotonin 2A receptor on neurons throughout the brain, which causes

- The neurons to fire more rapidly

- More effective neuronal communication between different brain regions

- Disrupted sensory processing leading to changes in sight, hearing, taste, smell, and touch

These changes in the brain lead to alterations in perception, thought, and mood that are characteristic of a psychedelic experience.

The discovery and synthesis of lysergic acid diethylamide (LSD) in 1938 by Albert Hofmann brought about a surge of research into the use of psychedelics in the 1950s and 60s. But this research was largely halted in the 1970s due to unsubstantiated concerns about their safety and potential for abuse. However, in recent years there has been a resurgence of interest concerning the therapeutic potential of psychedelics.

How Are Psychedelics Being Studied?

As of today, psychedelics remain a Schedule 1 drug in the United States, meaning that per the federal government, psychedelics have no medical value and hold high potential for abuse. Despite this designation, the study of psychedelics is acceptable under highly regulated and controlled circumstances. Anyone conducting research with these drugs must obtain approval from the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and request a Schedule 1 license from the Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA).

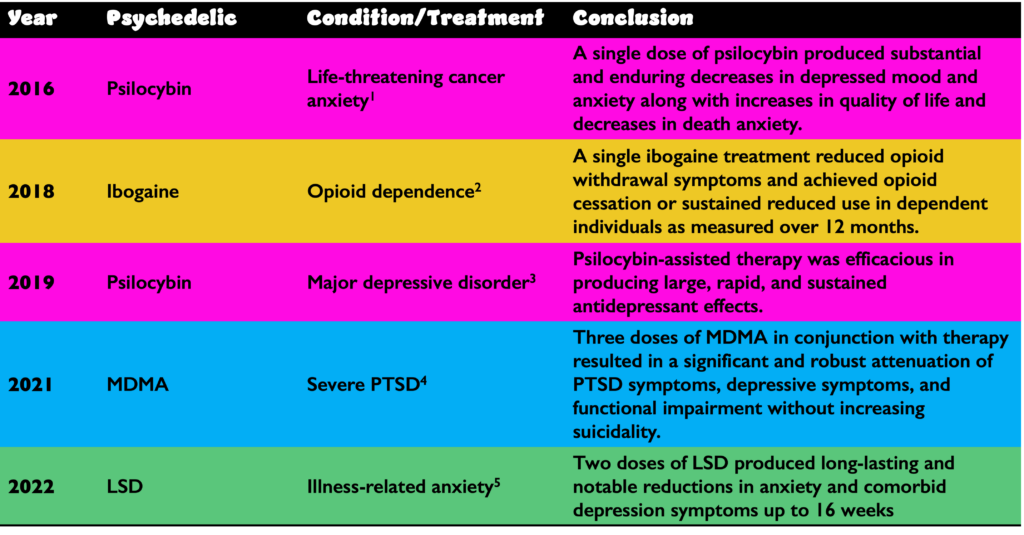

Several recent studies have shown the effectiveness of psychedelics:

LSD, lysergic acid diethylamide; MDMA, 3,4-Methylenedioxymethamphetamine; PTSD, posttraumatic stress disorder.

It is important to note that this field is still in its infancy, with the benefits of psychedelics yet to be proven in large, randomized trials. With psilocybin, the best-characterized psychedelic, several early-phase studies have been conducted. The most notable of these is a phase 1 study (NCT04052568) designed and conducted by Johns Hopkins University, investigating psilocybin in patients with anorexia nervosa.6

There are several explanations for why this field is moving so slowly, including but not limited to

- Legal and regulatory hurdles

- Difficulty blinding psychedelic trials because of the obvious effects of the drug

- Patient expectations of efficacy are often too high and not realistic

- Social perceptions as well as economic issues make enrollment challenging

- Requirement of special authorization to study a Schedule 1 drug

- Limited funding at academic institutions for the large trials needed to produce robust data

FDA Draft Guidance Concerning Psychedelic Clinical Trials

In an effort to highlight fundamental considerations for researchers investigating the therapeutic use of psychedelic drugs, the FDA recently released their first FDA draft guidance to industry for designing clinical trials for psychedelics.7 Key takeaways from the guidance include

- The FDA recognizes that psychedelic drugs have therapeutic potential for the treatment of a range of medical conditions

- The FDA is willing to work with sponsors to develop psychedelic drugs for clinical use

- The FDA has identified challenges that need to be addressed in the development of psychedelic drugs and provides sponsors with recommendations for addressing these challenges

It is important to point out the contradiction between the federal status of psychedelics as Schedule 1 drugs and the simultaneous FDA acknowledgement that these agents do in fact hold therapeutic potential. This will need to be remedied through federal law, opening the door to more pharmaceutical industry investment in clinical trials.

Conclusions

Our current knowledge of psychedelics owes much to our ancient ancestors’ wisdom in exploring these substances. Today, despite being classified as Schedule 1 drugs at the federal level, psychedelics are being studied more seriously for their potential to treat psychological conditions. The recent release of the FDA’s draft guidance for designing clinical trials on psychedelics demonstrates a growing recognition of their therapeutic potential. As we move forward, rigorous research will be essential to fully understand the advantages and risks of psychedelics, potentially leading to groundbreaking medical treatments in the future.

References

- Griffiths RR, et al. Psilocybin produces substantial and sustained decreases in depression and anxiety in patients with life-threatening cancer: A randomized double-blind trial.

J Psychopharmacol. 2016;30(12):1181-1197. - Noller GE, et al. Ibogaine treatment outcomes for opioid dependence from a twelve-month follow-up observational study. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 2018;44(1):37-46.

- Davis AK, et al. Effects of psilocybin-assisted therapy on major depressive disorder: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Psychiatry. 2021;78(5):481-489.

- Mitchell JM, et al. MDMA-assisted therapy for severe PTSD: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 3 study. Nat Med. 2021;27(6):1025-1033.

- Holze F, et al. Lysergic acid diethylamide-assisted therapy in patients with anxiety with and without a life-threatening illness: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase II study.

Biol Psychiatry. 2023;93(3):215-223. - Effects of psilocybin in anorexia nervosa. ClinTrials.gov identifier: NCT04052568. Updated: May 6, 2023. Accessed: July 21, 2023. https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT04052568?term=NCT04052568&rank=1.

- US Food and Drug Administration, Center for Drug Evaluation and Research. Psychedelic Drugs: Considerations for Clinical Investigations. Guidance for Industry. US Food and Drug Administration; June 2023. Accessed July 28, 2023. https://www.fda.gov/regulatory-information/search-fda-guidance-documents/psychedelic-drugs-considerations-clinical-investigations.

Aaron Csicseri, PharmD

Senior Scientific Director

Dr. Csicseri joined the ProEd team in November 2017 as a scientific director, responsible for scientific leadership, content development, strategic input, and effective moderation of team meetings. Aaron has extensive experience guiding Sponsor teams through the AdCom preparation process. He received his PharmD at the University of Buffalo, where he studied the clinical curriculum. Aaron has 10+ years of experience as a medical director/clinical strategist in the accredited medical education field (CME), as well as in the non-accredited PromoEd sphere. Over the past 6 years, he has been supporting Sponsors in their preparations for FDA and EMA regulatory meetings in a wide variety of therapeutic areas. Aaron is based in Grand Island, NY, just outside Buffalo.

Connect with Aaron on LinkedIn.